Scientists Unearthed A Never-Before-Seen Mineral Inside Of A Diamond

Diamonds are one of the most highly sought crystals in the world, with the industry earning $79 billion in 2019 alone. In 2018, scientists were searching for diamonds-- but not for money. They were more interested in the mineral inside of the diamond. Nobody had ever seen this mineral before, and its discovery changed science.

Perovskite, A Mineral That's Both Common And Rare

In 2018, scientists from the University of Alberta uncovered a never-before-seen mineral. That is not because the mineral is rare; it is actually the fourth most common mineral on Earth.

The mineral-- called calcium silicate perovskite (CaSiO3) or perovskite for short-- is so deep below the Earth's surface that scientists had never seen it in person before.

Professor Graham Pearson Knew Where To Go

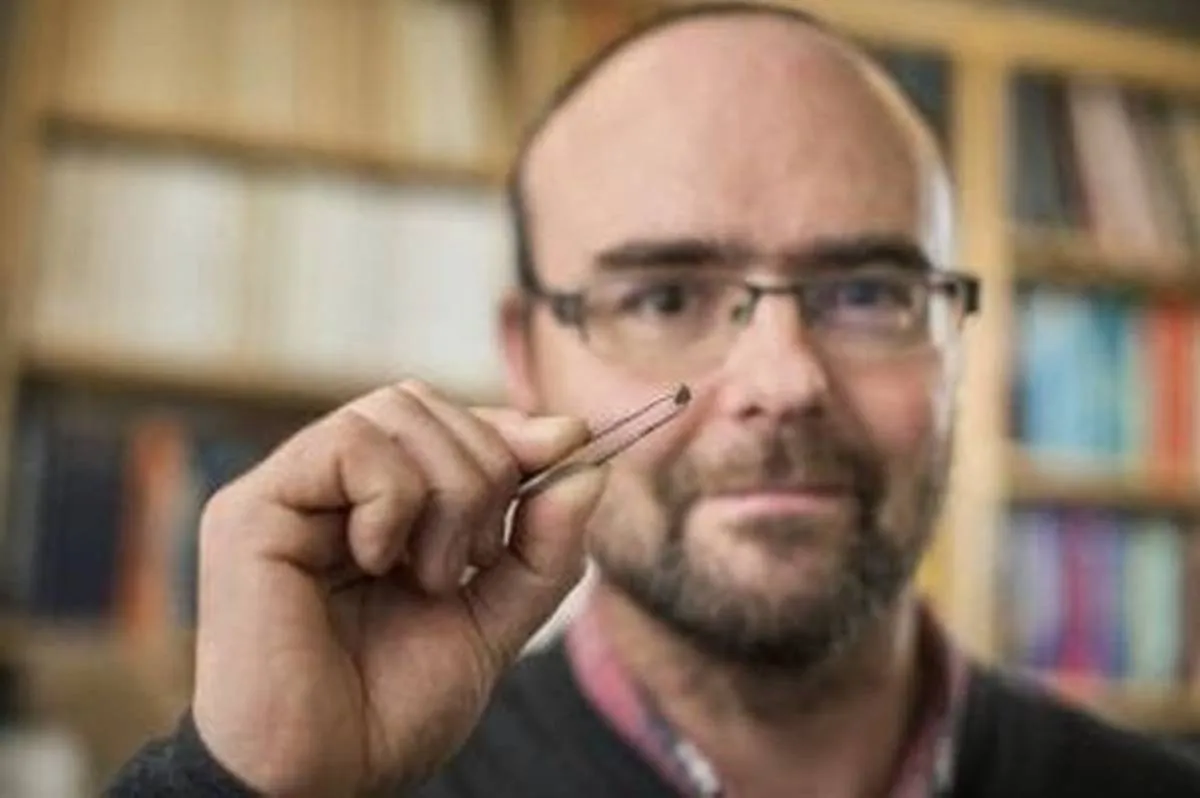

It began with a journey to South Africa. Graham Pearson, a professor of the University of Alberta's Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences and the Canada Excellence Research Chair Laureate, lead the expedition.

The team explored Cullinan Premier Mine in the Gauteng Province. There is a reason they chose that mine, specifically.

Cullinan Mine, The Source Of Royal Jewels

The Cullinan Mine was named after Thomas Cullinan, who discovered the world's largest rough diamond there in 1905. The Cullinan Diamond weighed 3,106.75 carats, or 1.4 pounds.

The diamond was cut into various sizes, and the largest sits on the British Royal Family's Sovereign's Sceptre with Cross. Queen Elizabeth II even has some on her crowns.

But For Scientists, The Cullinan Mine Was More Valuable

Although the Cullinan Mine is known for royal jewels, it also holds value for scientists. Its diamonds are one of the most commercially valuable in the world. But Pearson said that they are also some of the deepest.

Diamonds are strong enough to withstand intense pressure changes. Because of this, scientists can pull them from deep within the Earth's surface and explore what happens there.

The Cullinan Mine Also Contains A High Amount Of Diamonds

Cullinan Mine is not only known for royal jewels. It is one of the largest diamond hotspots outside of the United States.

The volcanic pipe provides enough pressure to create diamonds naturally. De Beers, the world's largest diamond producer, once owned it. But Pearson and his team were not going there to sell diamonds.

Why Were They Looking For Diamonds And Not Perovskite?

If perovskite is so common, why haven't scientists seen it? Pearson clarified, "Nobody has ever managed to keep this mineral stable at the Earth's surface."

When unstable minerals reach the Earth's surface, they undergo a process called weathering. In short, they fall apart. Scientists have not seen perovskite as it naturally occurs beneath the surface.

Pearson Had Found Rare Minerals Before

Pearson was one of the best diamond researchers worldwide. In 2014, he discovered the world's fifth most abundant mineral, ringwoodite, far beneath the mantle.

Pearson discovered ringwoodite inside of a diamond that was buried deep within the Earth. He believed that he could find perovskite by using the same methods.

Perovskite Has To Be Encased In A Diamond

Pearson believed that the only way to get natural perovskite was by getting it encased in another material. "The only possible way of preserving this mineral at the Earth's surface is when it's trapped in an unyielding container like a diamond," he explained.

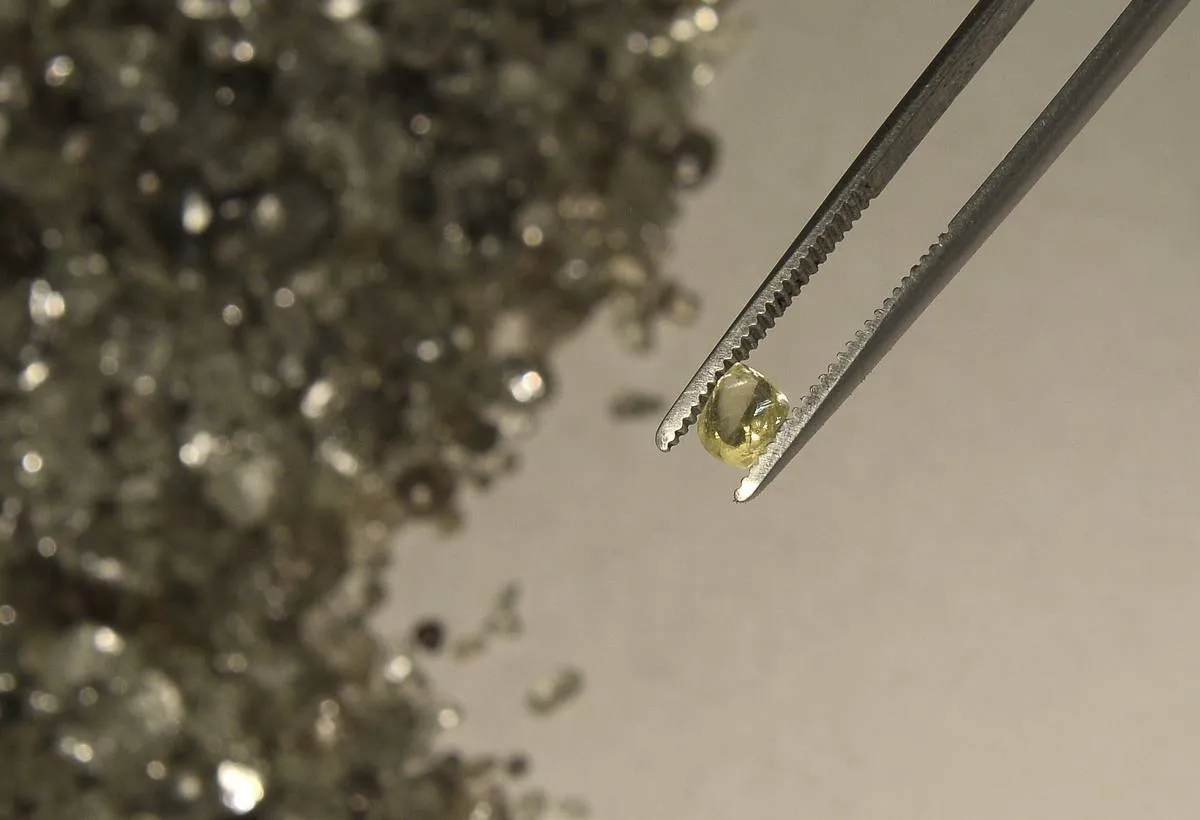

That is why his team went to Cullinan Mine: to unearth deep diamonds that hopefully contained perovskite.

They Had To Dig Much Deeper Than Usual

To find perovskite, the scientists had to dig much deeper than usual. According to Pearson, commercial diamonds are between 90 to 120 miles beneath the Earth's crust. But the team had to go over 400 miles deep!

Perovskite needs a lot of pressure--around 24 billion pascals, which is equal to 240,000 atmospheres. That is why no miner has ever seen one before.

430 Feet Below, They Found Something

Pearson teamed up with universities of Padua and Pavia, along with the University of British Columbia, to excavate the Cullinan Mine. They had to dig 430 feet below the surface.

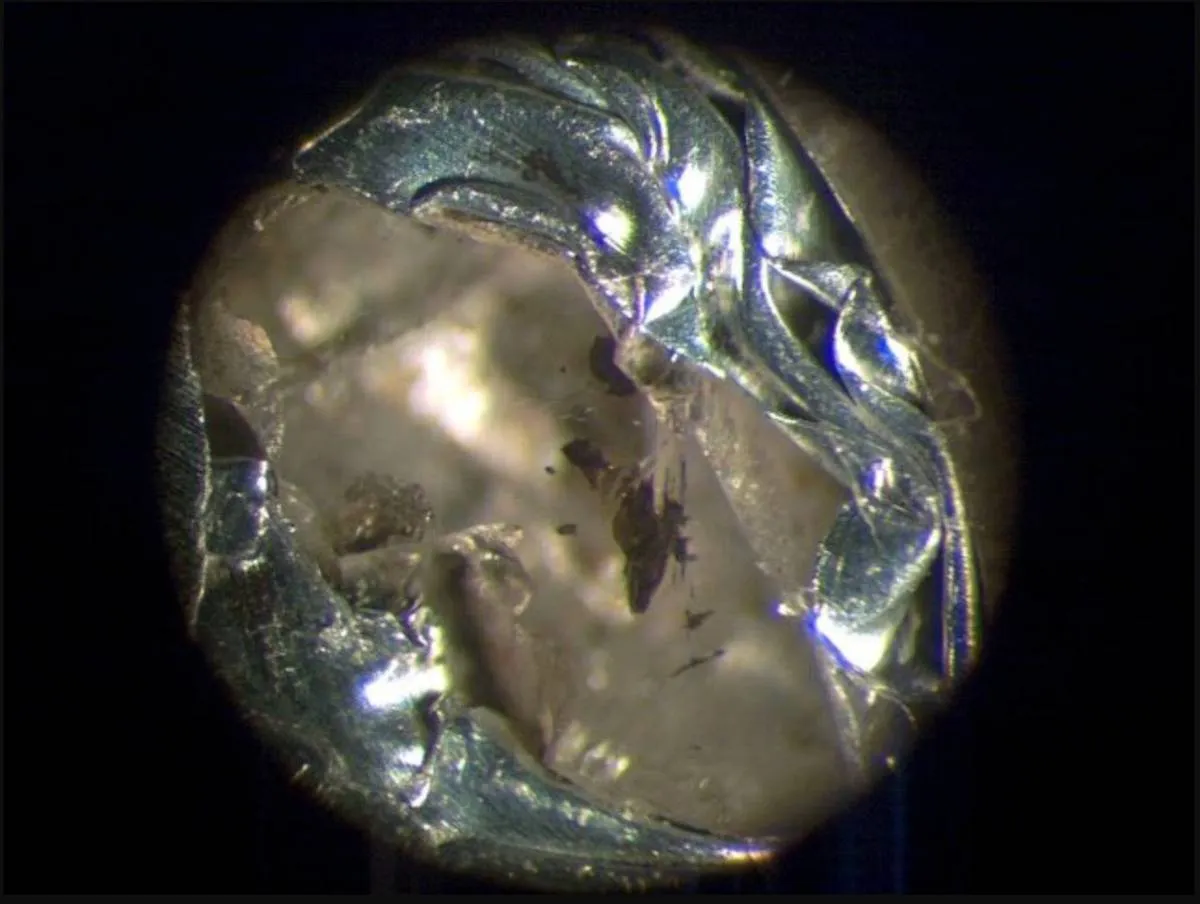

But when they did, they discovered a never-before-seen mineral. They unearthed a diamond with a piece of pure perovskite trapped inside.

Although Perovskite Is Common, This Finding Was Rare

As mentioned before, perovskite is common. Pearson estimates that the number is in the zetta tonnes, which have 26 zeros.

However, this particular finding was rare; not all perovskite gets trapped in diamonds. Fortunately, this allows scientists to view perovskite in its raw form, just how it appears in the middle of the Earth.

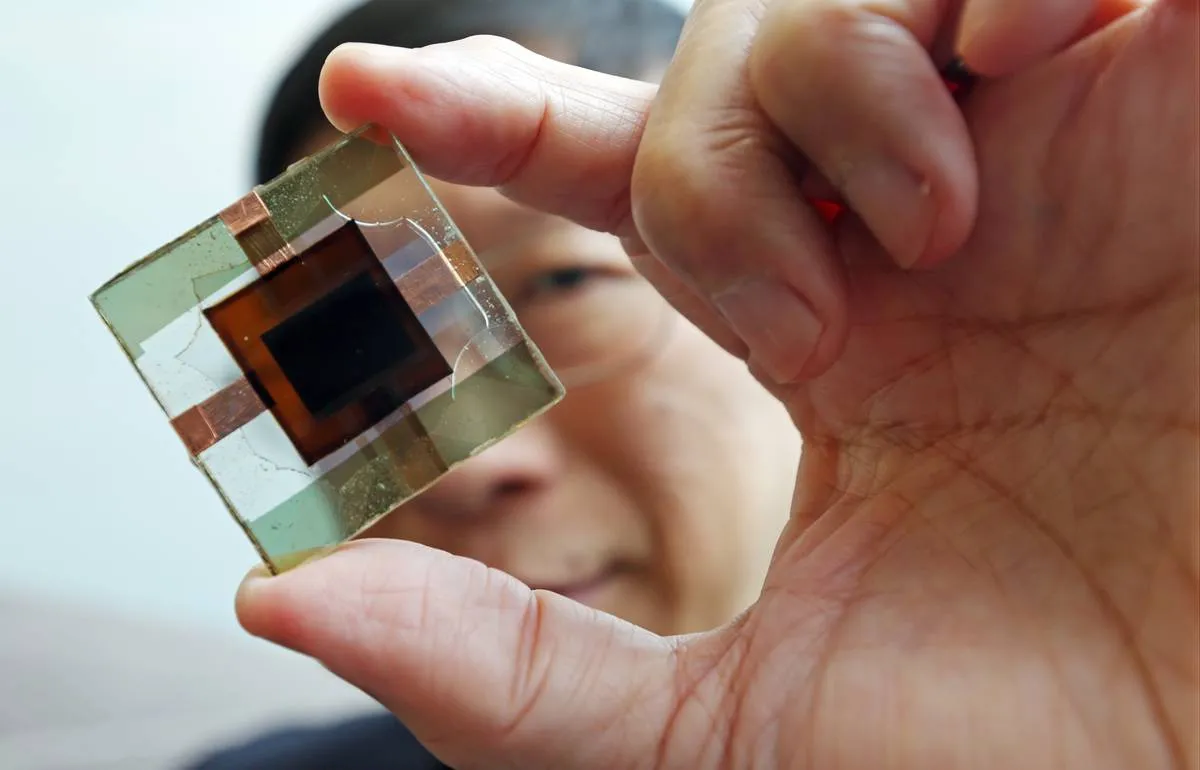

They Had To Examine It To Confirm

Although the scientists suspected that what they had was perovskite, they were not sure. After all, nobody had ever seen the mineral in person.

Pearson reached out to one of the best X-ray crystallographers in the world, Fabrizio Nestola from Padova, Italy. Nestola confirmed that the trapped mineral was indeed perovskite.

What Could They Learn From The Perovskite?

So kimberlites exploded, shot upward, and trapped perovskite in a diamond. But what does this provide for the scientific community?

For one, it proves that perovskite exists. The mineral has been suspected since 1839, as it was named after Russian mineralogist Lev Perovski. But 2018 was the first time anyone had seen it in person.

The Diamond Was Actually Formed Deeper Beneath The Earth

Although 430 miles seems incredibly deep, Pearson believed that the diamond actually formed even deeper beneath the Earth's surface.

X-ray and spectroscopy tests concluded that the diamond was more pressurized than it should have been at 430 feet. If that was true, then how did the diamond climb further to the surface?

How Did The Perovskite Get Trapped In Diamond?

Scientists immediately questioned how the perovskite got trapped in a diamond. Naturally-occurring perovskite lies deep beneath the Earth's crust, farther down than the scientists dug.

Although some suggested that the minerals gradually rose via churning within the Earth, Pearson rejected this. The process would be too slow. Instead, he had another theory.

An Explosion Occurred Beneath The Earth

Pearson believed that perovskite rose due to kimberlites. Kimberlites are rocks that contain diamonds, but when they react with high pressure, their dissolved carbon dioxide explodes.

"Some part of them starts life very, very deep in the Earth and literally blasts this thing toward the surface — the diamonds and the inclusion — and that's how you get these unique materials preserved," he explained.

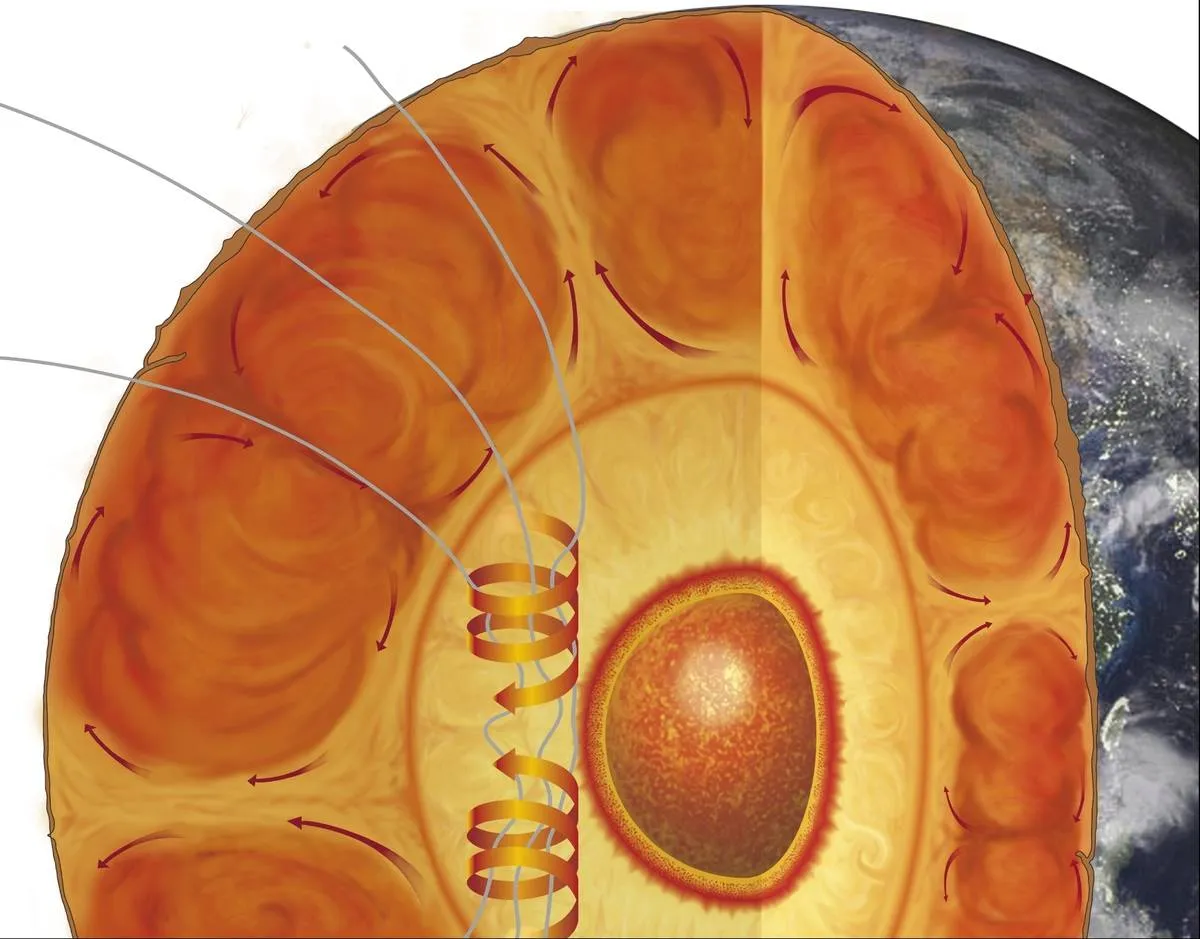

It Proved Recycling Within The Ocean's Crust

But perovskite is also evidence of a long-held theory. It proves that crustal recycling is happening beneath the ocean floor.

"[It] very clearly indicates the recycling of oceanic crust into Earth's lower mantle," Pearson explained. "It provides fundamental proof of what happens to the fate of oceanic plates as they descend into the depths of the Earth."

What Is Crustal Recycling?

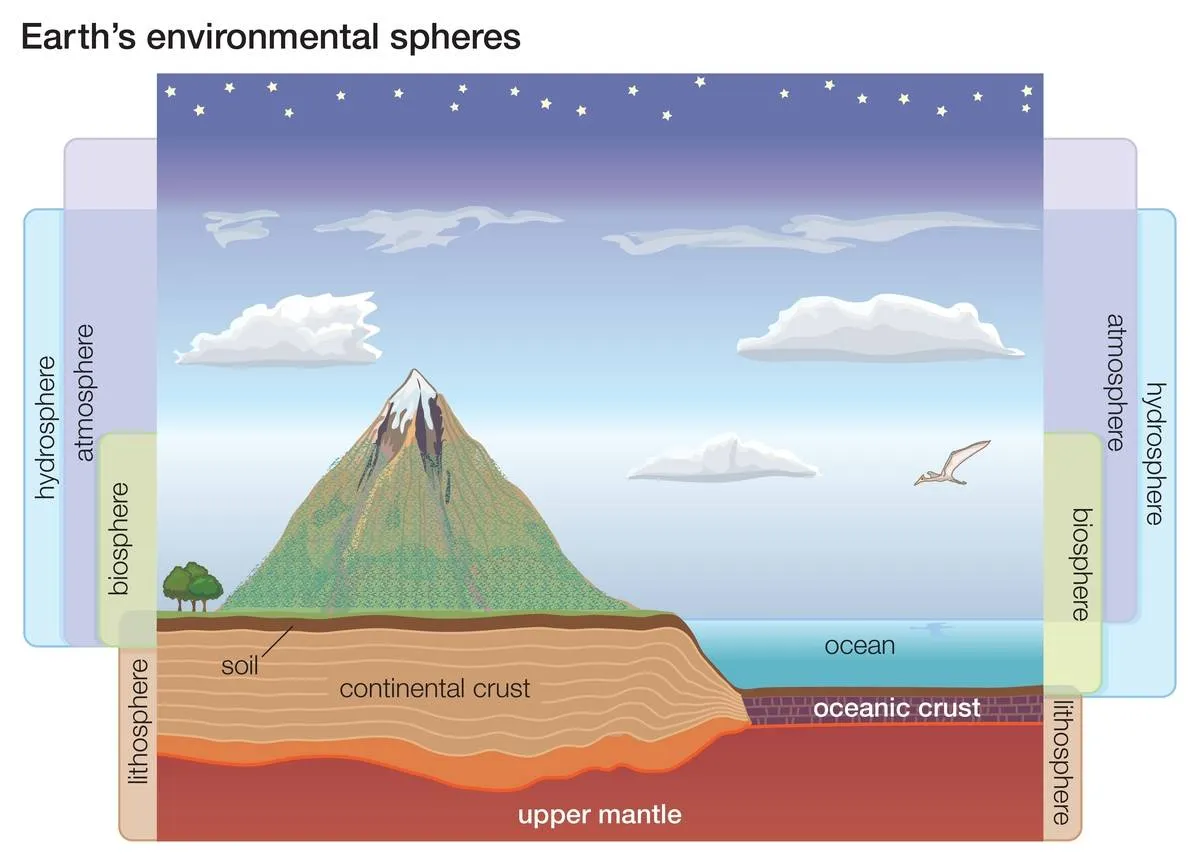

Crustal recycling occurs when minerals reappear near the surface. When tectonic plates move, some dive beneath the lithosphere (outer shell of the Earth) and into the mantle (the mostly-solid layer between the crust and the core).

When minerals go into the mantle, they eventually come back up into the lithosphere. That is what this perovskite proves.

Before Now, It Was Only A Hypothesis

Crustal recycling has been debated among the scientific community since it was pitched in the early 1900s. This newly-discovered perovskite provides solid evidence for it.

"It's a nice illustration of how science works, Pearson said. "That you build on theoretical predictions-in this case, from seismology-and that once in a while you're able to make a clinching observation that really proves that the theory works."

Perovskite Forms More The Deeper It Goes

Perovskite requires a high amount of pressure to form. Because of this, the average miner will not find fully-formed perovskite, no matter how deep they dig.

"When [perovskite] gets subducted down in the Earth's mantle, it keeps going until it transforms into higher and higher pressure mineral phases," Pearson explained.

Pearson Didn't Know How Old The Diamond Was

Oddly enough, Pearson could not confirm how old the diamond was. But based on radiometric dating methods, Pearson proposed that the diamond is "quite young."

Most diamonds that people wear as jewelry as three billion years old or older, but this diamond might be only one billion.

Finding The Age Of The Perovskite Was Harder

You might be wondering why scientists care about the age of the diamond. If they know its age, they might be able to estimate how old the perovskite is, too. After all, it's hard to test a mineral that they cannot remove from the diamond.

Pearson plans to study it further. "We have a program looking at super-deep diamonds with the purpose of obtaining information."

His Published Study Changed Science

Pearson published his study, titled "CaSiO3 Perovskite in Diamond Indicates the Recycling of Oceanic Crust Into the Lower Mantle," in the scientific journal Nature. It gave credence to the Crustal Recycling hypothesis.

"It provides fundamental proof of what happens to the fate of oceanic plates as they descend into the depths of the Earth," Pearson told CBC's Radio Active.

Pearson Is Training New Scientists To Get Perovskite

Since this discovery, Pearson has teamed up with colleagues from the University of British Columbia. He helps them run Diamond Exploration Research and Training School.

In this program, Pearson is training diamond explorers to find perovskite and ringwoodite. The next generation of mineralogists will likely discover more about the Earth's crust.

Diamonds Aren't The Only Valuable Mineral

Although the diamond industry is booming, diamonds are not the only valuable mineral. In this case, the diamond was the case that held the more significant crystal.

Perovskite is more common than diamonds, and yet it is under-studied, elusive, and difficult to find. As scientists research more of these minerals, we will understand more about the planet we share.